U.S. Climate Withdrawal:

A Strategic Opening for China

and the Middle East

By Jemima Oakey

15 January 2026

On January 7, the United States (US) government issued a presidential memorandum directing federal agencies to move toward withdrawing from, or ending US participation in or funding of 66 international organizations and treaties deemed “contrary to the interests of the United States” to the extent permitted by law. The list includes several key institutions that underpin global climate change governance, critical mineral resources and sustainable development – including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), and the International Solar Alliance.

The memorandum represents a significant retreat by the world’s second-largest carbon emitter from international climate cooperation. It signals a clear policy divergence between the US administration and the prevailing consensus on the threat of climate change and the risk posed to US interests. It is likely to significantly weaken global climate change institutions and risk undermining and delegitimizing their efforts. The resulting financial shortfall places jobs, research, and adaptation projects at risk, leaving the world more vulnerable to climate-related disasters that continue to grow in frequency and intensity each year.

In the ensuing vacuum, there is an opportunity for China to combine its leadership in renewable energy production and adoption with the readily available capital of its partners in the Middle East to offset funding shortfalls at international organizations and play a leading role in shaping global climate action and energy transition strategies.

China and the Gulf states are uniquely positioned to play a leading role in sustaining global climate cooperation

Why US Climate Withdrawal is an Economic Own Goal

The recent announcement is the most consequential step the US has taken to date on climate change. It is also counterproductive to US interests domestically, by further harming the US’ reputation with international partners, and in reducing the US’ ability to shape and lead international strategy on climate challenges.

Fighting climate change is not “contrary to the interests of the United States” as suggested by the memorandum. 2025 was one of the top three hottest years on record, and between 2018 and 2022, US climate disasters cost the country USD 150 billion per year. In 2024 alone, there were 27 confirmed climate disaster events, each resulting in losses exceeding USD 1 billion.

US Climate Disasters in 2024

The US withdrawal not only undermines global climate action but leaves the US exposed to further climate disasters, which will continue to cost the US and hamper its productivity and economic growth.

Critical Implications for Global Climate Action

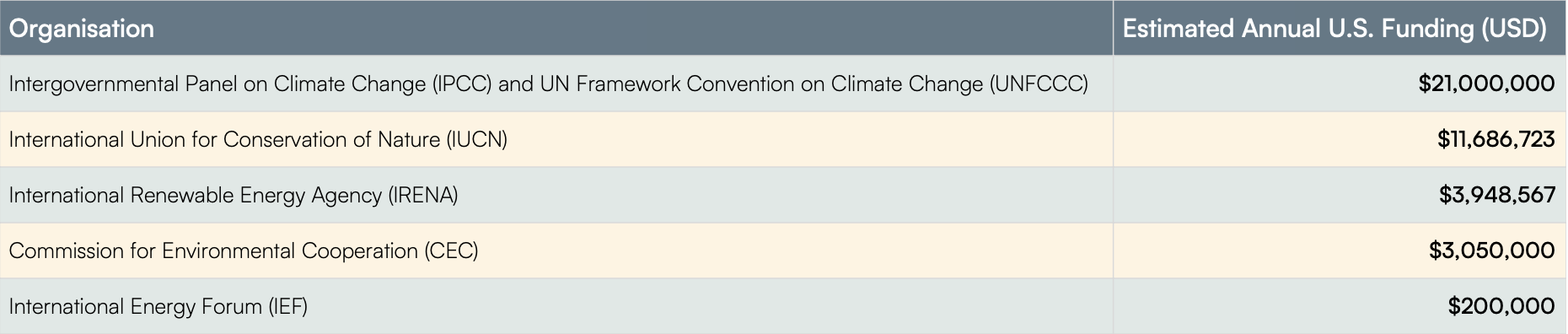

US funding for the international organizations listed in the memorandum represents a minor share of the federal budget, see Figure 2. Yet, the implications of the cuts for jobs, climate research and the continuation of mitigation and adaptation projects are severe. The decision comes less than a year after spending reductions implemented by the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), which resulted in the cancellation of almost 10% of global climate finance during cuts to USAID programs. During that period, 98% of USAID awards that included climate elements were cancelled, resulting in a climate finance deficit of approximately USD 11 billion per year.

Without these resources, conducting research and implementing adaptation and mitigation projects, will be extremely challenging. More broadly, reducing global carbon emissions without the participation of the world’s second-largest carbon emitter will likely harm international efforts to limit warming to 1.5 Celsius by 2030.

How China and the Middle East Are Poised to Lead

US withdrawal leaves not only a financial deficit, but also a lack of leadership at a critical moment for global climate action. In this context, China and the Gulf states are uniquely positioned to play a leading role in sustaining global climate cooperation while advancing their own strategic, economic, and environmental interests.

China and the Gulf states already maintain strong ties on renewable energy, manifested through joint ventures across the Middle East and Central Asia, large-scale green manufacturing deals, and high-level strategic cooperation on climate initiatives via the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

China also leads the world in clean energy supply chains. It is the world’s largest producer of solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and electric vehicles, and it dominates refining and processing capacity for many critical minerals essential to clean energy technologies. Domestically, China has installed some 887 gigawatts (GW) of solar power generation capacity – nearly twice that of Europe and the US combined. Internationally, it has expanded its footprint through energy infrastructure investment across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The industrial scale and technological innovation give it both practical expertise and credibility in guiding international climate research and policy coordination.

Kela Photovoltaic Power Station in Sichuan, China.

From a financial perspective, China possesses the capacity to offset the immediate shortfall in funding for the IPCC and UNFCCC. Whether it is willing and able to commit to matching the overall annual shortfall – in 2025, this was around $11 billion – amid low domestic economic growth remains to be seen. However, China needs not act alone. Gulf states’ readily deployable capital, combined with their economic diversification agendas and ambitious renewable energy deployment plans, positions them well to become leaders in clean energy and climate finance and to benefit from associated economic opportunities. Institutions such as IRENA, headquartered in the UAE, already anchor the Gulf within global climate discourses.

Dubai International Financial Centre district.

A coordinated China-MENA approach could therefore help mitigate the immediate funding shortfall left by US disengagement while reinforcing the legitimacy of international climate institutions. Crucially, by assuming senior roles as funders, hosts, and agenda and rule setters, both China and the Gulf states would be able to shape the direction of global climate governance, including the definition of transition pathways and the prioritization of adaptation finance – issues that intersect with their own domestic climate policies, energy security priorities, and economic diversification strategies.

Stepping into these roles would also provide direct benefits for both China and the Gulf states. Both face risks to their socio-economic stability from climate impacts, including extreme heat, water scarcity, flooding, and desertification. Strengthening international climate research and coordination directly supports their own adaptation planning while enhancing international standing, soft power, and diplomatic influence.

In this sense, stepping into the leadership and funding gap created by the US would not be an act of charity. Rather, it would represent a strategic investment in economic resilience, international influence, and climate stability – one that offers tangible benefits for China, the Middle East, and global climate action.

Jemima Oakey is a China-MENA Research Fellow at the Carboun Institute.